In this Episode

- [03:08]Rabbi Chaim Miller discusses Jewish spirituality and the concept of reincarnation.

- [05:54]Stephan shares what stems from his fear of water through past life regression hypnosis and opening his Akashic records.

- [07:41]Rabbi Chaim explains the concept of reincarnation and how it can help us understand our past traumas and current life experiences.

- [11:09]What is the Torah?

- [18:54]Rabbi Chaim discusses the two types of prayer and explains how prayer becomes a personal experience.

- [26:26]Rabbi Chaim explains Zohar– an ancient mysticism text introducing the idea of influencing God.

- [35:56]How can we transform our relationship with God?

- [47:56]Rabbi Chaim explains a mention of a satanic tradition in Judaism, which is present in the Talmud and other rabbinic texts.

Rabbi, it’s so great to have you on the show.

It’s such a joy to be here.

I have a lot to talk with you about. I’ve been getting great information and guidance on what to ask you for the week. I would love to start with a sticky one that some people might want to turn off the episode right now because they don’t believe in it, but reincarnation.

I know this is not seen as part of the Judeo-Christian religions. It is actually part of Judaism, and it’s not just Hindu. I’d love to hear your thoughts on reincarnation and thoughts that you want to share from the Tanya. Why do we have reincarnation? How does it work? Is it worthwhile to go back into our past lives somehow through regression, hypnosis, et cetera?

Great question. Let me start by saying that I think Jewish spirituality is hugely underrated. A lot of people don’t even know there’s such a thing as Jewish spirituality. It’s something that all the denominations of Judaism have in common, they all don’t really teach it. Whenever you’re going to go to a synagogue, it’s not really taught very much. There’s a huge textual tradition of Jewish spirituality. There’s also a living tradition, people practicing it. A lot of things we’re going to talk about are in that.

I have a friend from Australia, a rabbinic friend, who told me that he had an audience with the Dalai Lama about ten or 20 years ago. He asked the Dalai Lama, “When Jews come to you, why don’t you send them to their tradition? Why do you teach them Buddhism?” He gave two replies. He said, “First of all, they’re coming to me. If they had something in the Jewish tradition, they would have found it.”

“The second thing you said is that Western Buddhism is run by Jews, so the whole thing would fall apart if they didn’t come to me.” That anecdote struck me very strongly about how badly we are spreading this wisdom. Thank you for having me on today to try, in a little way, to redress that balance.

Reincarnation is a very extensively documented belief in the Jewish tradition, particularly the Kabbalistic tradition, Jewish mysticism. The deeper questions are in the Kabbalah, and it’s something a lot of people have heard of. The idea behind this is that we’re never born with a blank slate. Historically, we’re all born into a certain context. Like Billy Joel said, “We didn’t start the fire. It’s been burning since the world’s been turning.” You’re born into a mess, basically.

Spiritually, in terms of past existences, you don’t come in with a clean slate with your soul, either. You’ve been doing work in previous lives, either successfully or unsuccessfully. You’re usually coming back to work on something which you didn’t get right before.

The Jewish belief is that what you’re really here to do is probably you won’t enjoy that much, where you find it hard because it’s a muscle that you’ve never used in any life, and you’re coming back to do that particular thing. Everyone’s like, “how do I know?” There are always people who could do past life regressions, and people use astrology to find out information about their past lives, or some people just have intuition themselves.

I think it’s something important. This might be a little bit radical, but I think you can even bring in some trauma from past lives. I’ve definitely, in my experiences, been dealing with people and sense that some people are almost born with some traumatic death in their previous life, which is affecting how they’re working now.

We’re never born with a blank slate.

By the way, I found that to be true for me. My fear of water comes from at least three past lives where I died from drowning.

Wow. How did you find that out?

One of them I saw during a past life regression hypnosis session. That was my most immediate past life. I was dared to jump off a bridge as a teenager by some other teenagers, and I stupidly did it. Of course, I’m grateful that it happened because I’m here now in this incarnation. That was one.

I learned how to open my Akashic records and asked the record keepers, my guides, and was shown some images then of three other past lives, one where I was drowned. There’s one where I was sucked out to sea by the current. You know what? It wasn’t traumatizing. It was just like watching a movie. It didn’t feel like, “oh, that’s me. There you go.”

Does it affect how you relate to water now or being dead?

Yes, it’s so much easier. I feel at peace. Yeah, it just simply is now. I’m grateful for that.

Amazing. I think it’s an important thing that when you walk on this planet, you need to know where you’re coming from. For people who don’t believe in past lives, it could even be like an early childhood experience. The past life really begins, I would say, at the end of the age of two because you’re still ticking over, and that part isn’t remembered.

You’ve been doing work in previous lives, either successfully or unsuccessfully.

I do know somebody who remembers losing his sibling in the womb with him. Pretty wild.

In case you’re wondering where this comes from, in the 16th century, it was a major center of Kabbalah in Tzfat, Israel. All the Kabbalists had a belief in reincarnation, and the most famous is Rabbi Isaac Luria, who wrote a whole book on it called The Book of Gilgulim, the book of reincarnation. Gilgul literally means recycling, it’s just the turning around, which in Hebrew is a little bit more simple in the way it describes things, and therefore it’s actually more powerful. It’s just the recycling of life.

What goes around comes around. If you don’t clean up your messes in this life, you don’t get a free pass. Also, there’s a personal development expression, “success leaves clues,” I also think failure. But mistakes and missed opportunities leave clues as well.

They could actually leave clues in your body. You’re incarnated, you have this scar or this birthmark on the back of your neck, and that is not by accident. It represents where you may have been decapitated in a past life, and you never resolved that trauma. Now I have all this neck pain, and yes, I have a birthmark there. I have no idea what that relates to, but that’s just what I was born with.

It’s a way of understanding the personal relevance of spiritual teachings because, in all spiritual teachings, they’re talking about archetypes and energies out there in the universe. Jewish spiritual direction is no different. We have Ten Sefirot, ten energies, which are the fundamental building blocks.

People study this and say, “well, what’s it going to do for me? Am I connected to one of those in particular?” I understand the universe is built on that. I always imagine that these archetypes are the sea, and then I’m a boat on a wave in the sea. The sea churns up a certain recipe of those archetypes, maybe one or two in particular, and I’m riding on that. I’m trying to go from A to B, but the waves are pushing me another way because my past life experiences are the universe pushing me through that wave.

One book that might not seem related to Jewish spirituality, but I believe there is a connection there, is called The Body Keeps the Score. Are you familiar with the book?

Of course, yes. That’s still on the New York Times list about several years after. We’re just coming to understand trauma as a culture and how much of a major role it plays in so many people’s lives, even if it’s only the big “T” Trauma, small “t” trauma, or smaller events, which I’ve definitely experienced in my life.

Anything less than nurturing is trauma. What would you say is the point of having, let’s say, a birthmark or some clue relating to some past life trauma as part of your physicality?

I wouldn’t rule out that it could be. There was a lecture in Manhattan a few weeks ago by someone who’s an academic who had actually studied this phenomenon of birthmarks being a residue of previous lives. Definitely a possibility. I think that past life regression or using birth chart readings is the best way to go with understanding past lives. Judaism doesn’t have any particular tools for how to work out with your past life. Some people just know. They have deep knowledge.

And also, you can develop that.

Judaism would say it’s the thing that you’re resisting because in the Torah, which is the Five Books of Moses, the 613 commandments and the Talmud, which is the ancient rabbinic teaching says, there’s one of those 613 that is your personal one that you need to do. Not that the rest of them are irrelevant, but there’s one in this lifetime you need to do. How do you know what it is? The Kabbalists said, “It’s the thing you struggle with because the area of your struggle with the part of your shadow that you can’t own, is going to be hard because you have no experience in it.”

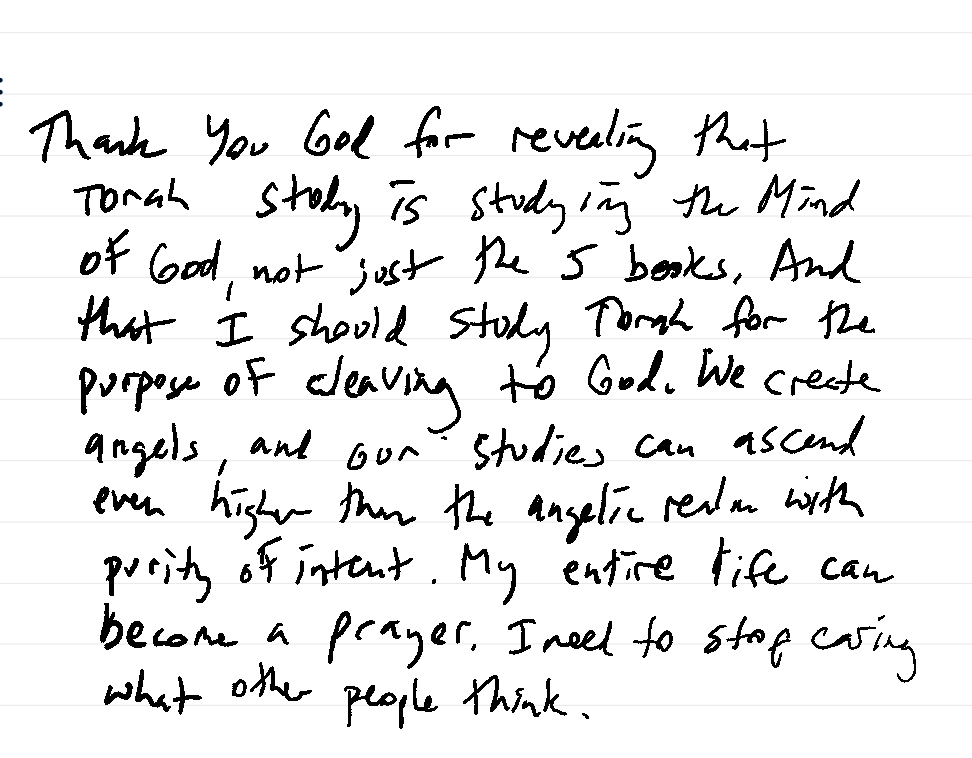

Actually, let’s move on to talking about the Torah. My understanding of the Torah is that it’s always growing. It’s not just the Five Books of Moses. It includes every book that analyzes or expounds upon the Five Books, or expounds upon some of the books that are about the Five Books. Another message that came to me from above is that Torah studies aren’t about studying the Five Books but about studying the Mind of God. Also, that I should study the Torah for the purpose of cleaving to God. I’d love to hear your take on all that.

Absolutely. There’s a lot there. First of all, Torah is really a conversation. The Torah was given at Mount Sinai in the month of Sivan, which corresponds to the astrological sign of Gemini. The rabbi’s thought is that it’s because Gemini are twins. It’s a conversation. It’s not a religion that says, ‘here’s the dogma. You have to buy this; otherwise, you’re not part of the religion,’ or ‘you’re not going to achieve salvation.’ It’s always been molded by the recipients.

It’s not just God speaking, and we have to listen. There’s a conversation. The largest Jewish text is the Talmud, which is about 500 years of just conversations about the text and molding their relevance to us. You feel that the rabbis at the time felt that they were equal partners or at least junior partners in interpreting the text. It’s not just something that has to be swallowed as dogma.

Yes, the Mind of God. Judaism looks at the Torah, especially The Five Books of Moses, as a sacred text. Even the Talmud was looked upon as a sacred text, even if it was written by a human discussion. The experience of Torah study is one of a mystical union because, in addition to the cognitive content of the word, there’s an energetic content of the letters.

The Rabbi Israel ben Eliezer (The Baal Shem Tov) was an 18th-century founder of the Hasidic Movement, which still exists today as a revival of Jewish spirituality. He taught that when you’re looking at the text, don’t just look at the meaning of the words. Focus on the energetic content of the letters.

He said that there are worlds and souls, and all these lofty energies are circulating. You can absorb that just by looking at the shape of the Hebrew letters, the sound as it’s reverberating from your mouth. Just listen to the raw sound because when you read from a Torah text, you’re attaching to something which has divine energy. Therefore, you said it, the Mind of God. That’s another way of putting it. I just like to look at it as more energetic content. The beginning of Genesis is when God creates the world with language. He creates it with a Hebrew sentence.

Right. The Hebrew letters actually existed before creation did.

Exactly. The Kabbalah teaches that the letters are really packets of energy. That’s what they are. God wraps himself up in these packets. Bits of God or emanations of God are wrapped up in the packets, and then the packets create the world. Language is not just a convention of why we call a table a table. There are some reasons for it, but it’s not particularly profound. But language is really divine energy, especially in the Hebrew language.

Our soul knows the Hebrew letters and knows Hebrew. Even if we don’t speak any of it, we scan the Hebrew letters of some sacred text and the energy transfers to us.

Exactly. Nahmanides, who was a medieval scholar famous in Judaism, said that the entire Torah is the Name of God, the whole thing. Why? Because basically, what is the Name of God? It’s a particularly high-energy set of consonants. When you say that name, you connect with a much more profound energy than the rest of the text. So, he said, “The whole thing is the Name of God. It’s all just a bunch of letters, and those letters are packets of energy, which somehow capture some of the energy of God.”

Hebrew language is a divine energy.

Amazing. I’m curious to hear what you think of this or what meaning you bring to this. I’ve seen Hebrew letters flying around, so I have some third eyesight. I’ve seen that over a person before. I’ve seen it in other contexts.

Really, what about the forehead? Have you seen Hebrew letters on someone’s forehead?

I have not. Have you?

No, I haven’t seen any of it. You’re the one that’s seeing them. Above the head?

Different letters float around above somebody’s head.

There’s a lot of discussion about this. I mentioned Rabbi Isaac Luria from the 16th century. He used to counsel people on this basis. He would count people in, and he would see letters somewhere around them and, on that basis, understand the person’s problems. This is documented.

We’re all psychic, though.

It’s true. It’s a muscle you have to develop. The Zohar says that when you go on a journey—I just learned this week, it’s fascinating—you are about to go on a journey in the morning, you should look at the morning sky before the sun actually comes up at daybreak, and it says you will see letters in the sky. If you’re really attentive, you will see that it’s the 42-letter name of God.

Before we get too excited in the Kabbalistic tradition, there are hundreds and hundreds of names of God, which have all different energetic formulations. One of the most powerful ones, which according to tradition, God actually used to create the world, has 42 letters. It says if you are intuitive, you’ll be able to see that, and that energy will give you safety during your travels. There are a lot of recorded traditions about seeing letters.

The 42-letter name of God is the basis of the Ana b’Koach prayer, which I say morning and night every bedtime and in the morning when I’m up and doing my morning connection.

The first letter of that prayer, Ana b’Koach, which is by Rabbi Nehunya ben HaKanah, who was a second-century mystic, is one of the earliest kabbalistic prayers that we have. The first letter of each of those words spells the 42-letter name of God.

By scanning the letters, as well as scanning the words of the prayer and pronouncing the words, even though I don’t speak Hebrew or almost none.

In a way, it’s better not to understand Hebrew because then you can focus on it as the energetic content. If you know what it means, then you get lost in the idea of it.

I love your analogy of energetic packets. As a geek, that appeals to me because I know all about IP packets and the internet protocol. Speaking of the Ana b’Koach prayer, there are two types of prayers. There’s one word for prayer in English, and that’s just a prayer. But there are two words for prayer in Hebrew. There’s the Hebrew word that begins with an H. It’s really hard to pronounce, but I’m sure you’ll help me with it. That means personal prayer, where you’re having that conversation with…

And the other one is for just traditional prayer. There’s a whole bunch of different prayers that you say when you’re, let’s say, consuming food, a drink, you’re washing your hands, you’re going to the bathroom, or whatever you’re doing, all these different prayers at different times. My understanding is that they’re tried and true frameworks, structures, or almost like standard operating procedures that plug you into the energy of the Creator.

Personal prayer is more like I’m just going to wing it and share what’s on my mind. If I have something to ask, I’ll ask, but it’s much about sharing what’s going on for me with radical candor, humility, and just putting it all out there and then listening for the responses from God. What’s the other word for prayer that’s the more traditional word?

I’d love to hear more about that from your perspective.

My initial reaction to formal prayers is that I don’t want to read some fixed texts.

I think they’re both very important, both personal prayer and using some traditional text. I prayed to God as a young child, just having a personal conversation. I’ve always found that very profound.

My initial reaction to formal prayers is that I don’t want to read some fixed texts. I want to talk to God. I think that sentiment is valid. Actually, if you look in the Torah, the Hebrew Bible itself, Abraham never praised. You never hear him praying. He just talks to God.

In some of the other biblical accounts you hear, they pray, they’re praying, they’re bowing, doing some ritual. But he’s just like, ‘Hey, God, what’s going on here?’ It’s like a conversation they have. When God wanted to destroy the city of Sodom and Gomorrah, he said, “Oh, how can I do this without telling Abraham?” They have this personal relationship. I think that’s 100% valid, especially in solitude, which is a practice of Hitbodedut.

Yes, Hitbodedut. I cannot pronounce that. My wife was trying to teach me that one.

That doesn’t actually mean “prayer”; it means “isolation.” It’s going into a field, into a space. If you’re in a city, I go on the roof, which is a quiet space, and just talk to God just candidly and honestly.

You have traditional prayers, which a lot of people have a bad experience with the synagogue being too formal and not really connected. I had a bad experience as a child. It wasn’t terrible. It was just not one of connection, one of just what’s going on here.

The way I look at the Hebrew traditional prayer book is, first of all, it’s ancient. This text obviously contains the prayers of different ages, but some of them go back a couple of thousands of years. They were written by people who understood the energies of the universe, people who were in touch with the mystical, the magical, and the sense of awe of nature. Somehow this has been encoded into the text in a way that there can be tremendous benefit from using something that is so old and so honed.

Prayer is a personal experience.

You have to do it in your own way. Even people who pray in the synagogue three times a day and they’re saying thoughts from the prayer, but even they have to do it in their own way because prayer is a personal experience. You need to find the prayer that speaks to you. You need to find a ritual that works for you.

Most people are not reading the whole thing every day. It’s very, very long. What’s important is to find… You said you read the Ana b’Koach prayer, for example. The Baal Shem Tov taught it’s better to say a little with a lot of devotion than a lot without devotion.

The power of intention.

Intention, yes. Kavanah in Hebrew, which literally means direction.

Right. That determines how far it reaches in the upper worlds, your prayer because it can get stuck at the top of the Malchut if you’re just trying to show up.

Baal Shem Tov once went into the synagogue and said, “This room is filled with prayer,” and they’re like, “Oh, great.” He said, “No, no, it hasn’t gone to the heavens. The prayer is still here.”

Intention is a very personalized thing. That’s why when the Hasidic movement came along, which was a revival of Jewish spirituality, they emphasized that you go to the synagogue but do your own thing so that you don’t have to worry about standing up at the right place and sitting down. Just do your own thing with the energy of the community because the personal connection is on board.

What about praying in a group? I know that there’s a certain power in having ten men gathered together in prayer at once, but even just a group prayer. Let’s say that there’s a hurricane on its way to Florida. A group of people praying for that hurricane to change course can change the course of the hurricane.

Intention is a very personalized thing.

Right. There is power in communal prayer. The idea is that there’s a bit of God in all of us. The more humans you bring together, the more divine presence you have just by manifesting through humans. That gives the energetic power. A critical mass is reached at some point that makes the prayer more powerful. Humans have known that for generations.

It’s important to remember. When you’re the lone wolf all the time, and you don’t bring in any of your colleagues to help with the prayer, it’s very important. The psychic medium put out a request to have everybody today at [11:11]AM pray for the dissipation or the movement of a tsunami that she saw was going to head to Africa, do a lot of damage, and take a lot of lives. I’m like, ‘of course, I’ll do it.’

I don’t see every email from all these different things that I subscribe to, but I saw that one. I know none of this is by accident. Everything is on purpose. Everything is divinely orchestrated. Nothing’s random.

There’s something more powerful about physical congregations. Virtual congregations are also good, but there’s something powerful about physically being present together. In the early synagogues, it still exists. They used to have a side room, which is off the main sanctuary, where people who just wanted to pray more at their own speed or do their own thing could do that, but still in the orbit of the congregation. It was called the Cheder Sheni, the second room.

A lot of people don’t realize that you can do that. They think, ‘well if I go to a synagogue, I have to follow the fixed prayers.’ I’m like, ‘I’ll do my own thing.’ No, you can actually go to synagogue, find a little area, and do your own thing there, but you’re doing it with the community, still.

That’s really cool. I did not know that. What would be some of the biggest secrets that, from your perspective, are perhaps transformational or life-changing in the Zohar, in the Tanya, and in these different sacred works?

There is power in communal prayer.

That’s a big question. The Zohar is an ancient text of Jewish mysticism. The main character in the text is Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai, a second-century Jewish teacher in Israel, just shortly after the temple’s destruction. There’s huge work, which was not very well circulated until the last few hundred years ago. It’s fascinating work. I would say the biggest secret that’s introduced there is that we can influence God, basically in a nutshell, and I’ll explain what that means.

Classically, Judaism is known as monotheism. We imagine God as being all-powerful and all-knowing. He’s not changeable because he’s perfect. What the Kabbalah does is it accepts that as true but paints another layer of divine emanation or divine energy, which is still within God. It’s not something that’s reached the universe yet.

God emanates within himself, but he’s not really gendered at that point. It’s called the Ohr Ein Sof, the Infinite Light of God. The infinite generates within itself some finite energies. They already have colors, shades, and qualities, but they’re still within God. They’re called the Ten Sefirot, ten divine energies. And then those divine energies create the universe.

What’s a great secret is that we can affect the alignment of these energies. Ohr Ein Sof, the Infinite God, you can’t really change or have it. It’s hard to have a direct relationship with. But what you can have a relationship with is the divine energies, which through human behavior, we can actually reconfigure these energies to be more in alignment, so there’s a more good flow to the universe. That’s the Zohar’s will view.

The idea of being partners in creation, which is probably a classic idea, you’re really a partner because you’re too dramatic, but you’re changing and affecting the divine. You would imagine that, well, I can’t change God. But you’re at least affecting the emanations of the divine. The Zohar is really a very long commentary on the Torah, discussing ideas implicit in the text itself and interpreting every verse of the Torah through that lens.

You mentioned Tanya. The Tanya draws on the tradition of the Zohar. Tanya is much more recent. It was published in 1796 by Rabbi Shneur Zalman of Liadi. He was a great empath. When people would come and seek counseling, he would absorb a lot of their pain. He writes this in a letter. At one point, he writes in a letter, ‘please don’t come to see me anymore because I’m just absorbing so much pain, I can’t cope.’

He had this idea, and this was before the self-help genre existed in Poland and Russia in the 18th century. He said, “I’m going to write a book which tells you what to do so you don’t have to come and see me, which I can’t go with.” So he possibly wrote the first self-help book, definitely in the Jewish tradition.

He uses Zohar’s idea of the ten Sefirot as also a picture of the human psyche. Everyone knows the beginning of Genesis, which says that humans were created in the image of God. What does that mean? The way that he reads it is that just as God has ten Sefirot, ten energies, which there’s a lot of detail about since we were created in the image of God, we have those ten energies. We embody those ten energies, similar to the chakra tradition in Eastern mysticism, as energy centers in the body.

He really writes, which is probably one of the earliest books of psychology. Tanya, the early work of Hasidism, is the psychological term in Kabbalah. It uses the Sefirot model as a guide to the human psyche. It’s not arguing with Zohar, and it’s just adding another layer.

Interestingly, Carl Jung actually picked up on this. If you read his 80th birthday interview, it is actually printed. He actually said the following, he says, everything I taught was anticipated by a very wise rabbi, and his name was Rabbi Dov Ber of Muzirich. If you open up the Tanya, on the first page, it says, this is the teachings I heard from Rabbi Dov Ber of Muzirich.

I don’t know if he actually saw the Tanya itself or other teachings circulating because there were some things available in German then. I don’t know exactly. He said a very strong statement that 100 years before Western psychology started to blossom, there were these rabbis in Eastern Europe who were really onto similar ideas.

The Tanya was really written as a therapeutic work. He writes in the introduction that basically when people come to see him, I give them advice to solve problems. I’ve just written this advice in a book. It’s just a collection of all the different types of advice that I’ve given people.

The reason why I think it was successful is he didn’t publish it straight away. He spent 20 years working out what bits of advice work and what bits don’t. Eventually, he published it. It was the first book that I discovered when I was about 20 years old. It totally blew me away because the upbringing I had with Judaism is basically a club. We went to synagogue, but it’s just basically kiddish, a social grouping.

I never noticed any interesting or intelligent ideas. The Torahs were all in antiquated English, and I couldn’t even read them. It’s a club. It has its advantages and disadvantages. It’s basically some sort of social grouping. When I was looking for the meaning of life in college, I never really thought of Judaism. I’ve checked that out.

I discovered, first of all, Maimonides’ The Guide for the Perplexed, which is actually out there amongst works of philosophy toward universities. I was shocked by it. What, rabbis wrote a book they’re studying in the university? My rabbi just talks about nonsense. That woke me up, and there’s an intelligent Judaism. But then, when I discovered Tanya, it was a combination of psychology, understanding the human condition, understanding the struggle, making realistic goals and self-improvement, and it was also philosophical.

It has the Maimonidean sophistication, but it also has Kabbalah, which is mysticism, your spirituality. It was all integrated together into one system. I found that very, very powerful. That led me to devote my life to it. I was not really looking to do this. I wanted to be a doctor. That didn’t happen. I ended up translating Jewish spiritual books.

While God hopes we choose the positive direction, he provides the negative pull to give us a free choice. Click To TweetWow, what a difference in the world you’re making because of it.

It’s so nice to know that you discovered this book and invited me to the podcast. It’s a lonely job. I just sit in this room, solitary confinement. I just sit and write. I know that somewhere someone is reading it, but most people do not reach out and say, “I read your book,” or they read some other book. Did you email the author to say you liked it?

I got guided to contact you from above, for sure. This is a fun trivia thing. When you were talking about trying to find the answer to life or however you framed it, there’s a book in the science fiction genre called The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. Are you familiar with it by Douglas Adams? Do you know about supercomputers?

Of course, I grew up on that. It’s on BBC too. The truth is, I had a flashback because when you use ChatGPT, it’s exactly the computer they had in The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. When they asked what the meaning of life and, he said 42…

Exactly, it’s the 42-letter name of God.

Yeah, which is in Hebrew. It’s the numerical value of Google, I think. I have to check that up. There’s a 42-letter name of God. Forty-two is important in Judaism.

I looked up Douglas Adams’ inspiration for coming up with 42. He said, “I don’t know.” He was just looking out in the garden, trying to think of what the supercomputer would answer with after all those millions of years of computing. It just came to him, 42, and then he puts it into the book. We oftentimes receive information coming from above, and we don’t realize it. We just think, ‘oh, that just came out of my brain.’

Yes. There’s a saying for that. Actually, there’s a play on Broadway now called The Wanderers. It’s about Hasidic Jews, Secular Jews, and the interactions I went to see.

It’s based on a Talmudic quote, which they keep saying throughout the play, which I don’t know if anyone knows what we’re talking about. Ein baal ha nes makir be’niso, which means when you have a miracle, you don’t realize it yourself. The one to whom the miracle occurred doesn’t recognize it. We’re constantly getting vibes from beyond, from the collective consciousness.

Amazing. I want to go back to some of the teachings of Judaism that are core fundamentals, one of which is teshuvah. It’s oftentimes translated as repentance, but in actuality, the word means “to return,” so you return to God. It’s very, very powerful.

I think it was Rambam who said that as an answer to the question of when you should do teshuvah, he said, “The day before you die.” The answer was, well, I don’t know when I’m going to die. Well, then every day. Any day, you might die.

What teshuvah incorporates isn’t just repenting for your sins, but also a deep sorrow, or I’m not sure if sorrow is the right word, but humility like ‘I’m really sorry, I’m really, really sorry’ and to mean it, to really embody that, and also to have a deep desire never to commit that sin again. If somebody cheats on their spouse, they will be tempted. That’s a guarantee. They will be presented with a similar or even more tempting opportunity to commit the same sin because that’s how it works, apparently.

It says that if a person had a sin with someone else, but if you meet the same person in the same place, in the same context, and you don’t do it, then you know you’ve done teshuvah.

Let’s talk about teshuvah and how that applies to everyone, not just to Jews, and how it can transform one’s relationship with God and with everything and everyone.

It’s such a powerful idea. It’s so multifaceted. I don’t know where to start. The simple meaning is penitence or asking for forgiveness, a feeling of distance. Teshuvah is a belief, it’s not just a way of behaving. It’s a belief that if I sincerely want to connect with God and I sincerely regret doing something wrong, then I will be forgiven. Otherwise, we could just hang around forever feeling like, ‘oh, I’m carrying this burden, and I’m a bad person.’ No, you’re not a bad person. You might have done a bad thing, but the teshuvah will eliminate that bad thing.

“Come close and come clean.”

Forgiveness holds incredible power in both human-to-human and human-to-God relationships. Click To TweetI liked when you said that it means return rather than repentance. It can mean both because it implies that we always want to come home. We want to get back to our essence, and we want to be true to ourselves.

There’s a mystical idea that teshuvah could be split into two words, which are “teshuva” and just the “h” at the end of “heh” in Hebrew, “teshuv-heh.” What that means is to return the “heh.” The meaning behind that is that “heh” represents Shechinah. Shechinah is the divine presence in all things. It’s the divine feminine, but it’s the way that the divine manifests in the table, in a chain, and in every single thing in the universe.

If we did something that makes us distant from God, what we’ve done is we’ve damaged God’s name. God’s name, tetragrammaton, is “Yod,” “Heh,” “Waw,” and “Heh.” The last “heh” of the four-letter name is Shechinah. By doing something wrong, we betrayed ourselves or betrayed someone else. We dislocated that “heh,” and we fragmented the name of God. By doing teshuvah, teshuv-heh, we return the “heh” back to God’s name. That is a more sublime way of looking at it.

My personal experience is that people in the teshuvah mode often don’t get the message that, like, teshuvah’s over now. You came back, you’re okay now, and they’re always like that repeatedly. That’s why, like I was stressing just before, it’s a belief in reality and the power of forgiveness.

Forgiveness works between humans and humans, between humans and God. When you’ve committed not to do something wrong again, and it’s a firm commitment, that’s it. It takes one second to do it. It says it all. You do it in one second. You’ve done it. It’s not like there’s a long thing.

In the olden days, it would sit in a sack. But nowadays, we get depressed or feel distant. No. In one second, you can decide, “I’m not going to do that again,” and then believe that you’re now close to God.

And that you’re worthy of being close to God.

Exactly. She was coming from worthiness. That’s why it shouldn’t be abused to glorify your lack of self-worth. It’s like, “oh, I’m doing teshuvah. I feel so lousy.” No, you have to work on self-love.

Teshuvah is not an excuse not to work on self-love. It’s actually a form of self-love that I’m going to credit myself with being okay now, that I’ve decided to shift away from a certain error, even if I mentally return to doing it again. I could be better. But for now, I’ve decided I’m not doing this particular thing, and then I want to feel the joy that I’m close again.

No beating yourself up. That’s not what teshuvah is about.

Not too much, just a little bit, but some people are addicted to it.

I want to go back to something that you said about the Shechinah and it’s in everything. I learned, not necessarily from Kabbalah, but from other mystical texts, that everything has consciousness. The trash you take out to the curb, the plastic toy that your toddler plays with, everything has consciousness, not just the people that you speak to.

Some people don’t even really think about their pets or different animals as being sentient or conscious, but they are too. It’s quite a mental leap to think that the plastic toy my kids are playing with has consciousness too. Maybe he’s not making it up when he’s having a conversation with that toy truck. It could actually be talking back to him. Let’s talk about that.

Yeah, this is a fascinating idea. Again, it’s all over the Jewish tradition. Even Maimonides, who was a rationalist, was not a mystical thinker. He wrote that the planets have consciousness.

That’s actually written up in the book A Wrinkle in Time by Madeleine L’Engle. Have you read that novel?

Even the things that don’t verbally speak to us, they speak to us in other ways.

No, but it’s similar to the Gaia hypothesis, which is similar to that. In their mystical tradition, we have this idea that even an inanimate rock and where it’s put has consciousness. You pulled out a Tanya there, but there are actually several books of the Tanya. It’s the biggest one. But if you get to number two, it’s about this topic, how there’s consciousness and everything. The example he gives there is a rock.

I’ll just tell you a funny story. The person who was translating it, his name is Rabbi Mangel. He’s a Holocaust survivor, and he’s still alive. He lives in New York. He was translating this book in the 60s or 70s. It says that everything has consciousness, not just humans, not just animals, not just the vegetable kingdom, but then in Hebrew, also inanimate objects.

In Hebrew, the way you say inanimate is domem, which means “silent.” That’s actually implying that it has consciousness, but it’s just not saying anything. In English, we use the word “inanimate,” which basically has no soul. That’s wrong.

When he was translating this, he gave it to his teacher, who was the Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, who was editing it. The rabbi edited it, and he crossed that you can’t put inanimate because the whole point of the book is to say that a rock has a soul, that a rock has consciousness. For that translation, it’s going against the whole grain. You have to put that the rock is silent.

I think it’s just a wonderful way of looking at things. Even the things that don’t verbally speak to us, they speak to us in other ways. The consciousness of the object is the spark of the divine that creates it. This is one of the fundamental differences between a mythical worldview and the classical worldview in Judaism.

The classical worldview is, as it sounds at the beginning of Genesis, God created the world, and then he sits back. He’s like the lifeguard by the pool. He’s just sitting there. If he needs to intervene, otherwise, he just lets you swim.

God is Being, and we’re being.

The mystical understanding is that creation is a constant process. He’s constantly saying, let there be light and all the other statements of Genesis because if he stopped pumping the energy into the universe, the universe would cease to exist because belonging to God. God is Being, and we’re being. We owe our being to the Supreme Being.

This is a constant process. The rock is only there because God is giving us energy. That energy is a form of consciousness.

And everything is of God. There’s nothing that is not of God.

Exactly. This idea now brings the presence of God into the everyday, mundane tables and chairs, not out of the heavens, but not just in the heavens. For Maimonides, the rationalist position was that you can’t say anything about God. If you say “God is great,” you’re going to imagine what a human says when they’re great? “Make America Great.” That’s what you’re going to be. That’s going to corrupt God with something that is human.

What you can say is he’s not stupid. You can’t say he’s intelligent because intelligence is something that you associate with humans. That’s great if you want to be textbook correct. But what you’ve actually done is you’ve distanced God because now, if you can’t say anything about him, how can you have a relationship with him?

The Hasidic rabbi is going in the opposite direction. God is in a stone in front of you, and he’s in the river, he’s in the tree. Of course, he’s in the birds and the animals. We’re living in a universe that is saturated with the divine, and you just have to peel away the superficial sensory reading of things to understand that pulsating energy underneath, which is the reality.

Given that, then wouldn’t God also be within, let’s say, Satan, within a negative entity?

Good point. I was just going to say, the Zohar, which is this shelf of mystical text, which is all about basically how to come to the mystical understanding of God, page one, you think, ‘oh, I got this great book on this,’ what does it begin with? It’s a description of a flower, how many petals it has, what color the petals are, and the sea pulls underneath. It’s a meditation on a flower.

Basically, what Rabbi Shimon ben Yochai’s saying is you can find God in flowers. You don’t have to go any further than that. Actually, flowers are such a beautiful thing. It’s very easy to find God. That’s an example of finding God in everything.

Within Satan, nothing is made of anything other than God because God is all that is. There’s nothing outside of God, so Satan is made from God.

It is a tough point.

In fact, I’ve heard a Kabbalah teacher explain that Satan is a positive angel.

First of all, most people don’t know there’s a Satan tradition in Judaism. I think it’s a purely Christian idea, but it is mentioned in the Talmud, in the classic rabbinic texts. It’s also mentioned in Zohar. The way it’s perceived is that satan, I’m just going to call it negative energy.

There are many names written in Hebrew. It’s called the “Kelipah,” which means “the shell” or “the peel,” because it’s concealing the truth in essence. It’s also called the “Sitra Achra,” which means the other side. I’ll just call it negative energy because it’s more relatable. What is that doing here? Basically, negative energy is on God’s payroll. Excuse upon. It’s a necessary evil.

Yes, because everybody and everything works for God, including satan.

There needs to be an opposite pull away from good things. Otherwise, we would have no agency. God is hoping that we go in the positive direction, but he nevertheless has to provide the negative side with some pull in order to give us a free choice. The way it’s described is when he gives these negative energies their salary, and the Kabbalah says it’s like throwing something behind your back to someone who you hate. You owe them some money, and you’re going to pay them the money. I won’t even look at it.

He’s not giving that energy to the negative force. He’s willing with warmth, with joy. He really doesn’t like doing it. He doesn’t like these forces because they’re making people bad, but he knows they’re necessary, so he throws them behind his back. Ultimately, they don’t have their own free will. They’re doing the work of God, but we don’t see that.

The analogy that’s actually given in the Zohar is that a king wants to check the sexual fidelity of his son. He hires a prostitute to seduce his son to see because when he’ll become king one day, he’ll have these temptations, and he’ll be able to overcome them. You’re thinking, what happens? It’s not an actual story that happens.

The King’s paying the prostitute and he’s hoping she’ll fail, but he needs to do it to test the son. That’s really what satan or the negative force is. God is hoping these forces won’t do their work, but he has to put them in place in order just to give us the ability to own our own narrative. We really wouldn’t own our own story if nothing was tempting us away from wholeness to our darker side.

Another way to refer to the dark side or whatever is “the opponent.” This is different from the devil in Christian understanding, correct?

It’s not dualistic. There’s no separate power in Satan outside God. I don’t know what other traditions exactly, how they understand them. In the pure monotheism of Judaism, they are on God’s payroll. That’s the way I put it.

Where does Gehinnom fit in?

Gehinnom, which is “hell,” is called purgatory in Victorian English, which means a purge is a cleanse, a detox basically—what happens is the soul when it goes through the world, even if a person is really pious or supposing someone never does anything bad, the soul goes to heaven at the end of their life. The soul still needs detox because you’re involved in the physical, and the mundane takes a toll on the soul, which is very pure.

There’s always some level of detox. The Gehinnom is the harsher detox, where you get really pushed. It’s a bit like, have you ever seen The Biggest Loser on TV? They really push people. It’s an intense detox.

I think this is an important concept to convey that Gehinnom is not hell in the sense that most people think of. It’s a way to climb the ladder to God. It is a purification step that if we’d have gone astray, you do the time. It’s for concealed time. It’s not forever. You’re not damned for eternity, and you get a maximum of 12 months.

No, it’s six months or a year maximum. It’s a relatively fast detox process. If someone’s going on a juice fast, they don’t say, “oh, I’m punishing myself for eating too many toxins.” They just have the joy that I’m cleaning my system out. That’s really the way I look at it.

Recognizing and healing trauma is a crucial process: Trauma is a generational issue that creates a divide between those who prioritize trauma recovery and those who don’t. Click To TweetIt’s a refreshing way to look at the terrible concept of hell because the hell that most people think of doesn’t exist. It’s not eternal damnation with brimstone, and fire, it’s run by the devil, and everybody is screaming in agony for eternity because they weren’t worthy of being saved.

Right. When you’re an author, you imagine that hell is you don’t get published, and heaven is you get published.

Where does self-publishing fit in? Is that purgatory?

That’s the way I see it.

I’d love to address this concept of, in trauma, you might leave a piece of your soul behind. It’s not just a new age concept of soul retrieval being like, ‘oh, I got to retrieve those parts of my soul,’ that actually comes from Kabbalah. It’s Jewish mysticism. I’d love to hear your take on that.

Before we get to trauma, the idea of the soul being the body is not a one-off thing, you get born, and the soul comes in. There are many layers to the soul. As we go through life, we gradually earn more or different layers of our souls.

In Hebrew, you have terms like nefesh, which means “the basic body intelligence.” Then you have ruach, which literally means “spirit,” but that means more emotional awareness. Neshama means “intellectual awareness, self-consciousness,” and also some spiritual understanding. And then you also have parts of the soul that never come into the body, but they’re connected to the part of the soul and your body like auras around your body, which you also benefit from. One of those is called chayah, which is “the aura,” basically. And then yechidah is something that threads through all of them. It’s the channel of connection that allows all the parts of the soul to connect.

Life is really trying to make peace between the soul and the body and to bring more soul into you.

Life is really a process of trying to get more soul into your body or different layers of the soul. Something as tragic and difficult as trauma will obviously set that back. It’s actually called “soul loss” in Judaism. It’s more just the lack of the ability to draw the soul into you, like failing to develop soul-body relations properly.

Some of the rituals in Judaism, like circumcision, the Bar Mitzvah or Bat Mitzvah, are actually major points in new soul injection into the body. The Sabbath, for example, Shabbat kept on Friday night. Saturday is also a time when you get more access to different parts of the soul.

Most people imagine if they believe in a soul, they just think, ‘oh, well, you get it when you’re born, and you lose it when you die.’ It’s not that simple. Life is really trying to make peace between the soul and the body and to bring more soul into you. Obviously, trauma, which is a shutdown of part of you, is a very serious soul loss.

Our culture, I would say, last ten years or so. It’s just really coming to the consciousness and awareness of how traumatized a lot of us are. Did you see that Prince Harry is actually doing life with Gabor Mate, who is a Jewish speaker on trauma. Do you know who Gabor Mate is? His recent book is called The Myth of Normal.

Yes. I haven’t read it yet, but I have it.

It’s fascinating. I read a lot of it. I think it’s Saturdays, and he’s doing life with Prince Harry to talk about trauma. They don’t do lives, maybe recorded beforehand.

Every so often, something rises to the cultural consciousness that shows that it’s the work of our generation. I believe that healing trauma is really noticing, and healing it is something that is a generational thing that almost applies to everyone. It’s a generational divide.

Our parents’ generation they don’t really get that. The post-holocaust generation was very much kind of. It doesn’t matter if you lost three-quarters of your soul, the bit you’ve got left. Just use that, and you’ll forget about the rest. It’s just survival or basic recovery.

Today, especially in my kids’ generation, no one’s interested in that. They want to own the whole of themselves. It’s about wholeness, which in Hebrew is shleimut, which is from the word shalom. It’s interesting. Peace and wholeness are the same things in Hebrew. It says after Jacob fought with the angel, he came with shleimut, which means “wholeness.”

That’s what we’re looking for, to own all of ourselves.

Inevitably, our parents didn’t always know what they were doing, and life throws that stuff at us. All of us have parts of our souls that need retrieving. Through journaling, meditation, prayer, through spiritual teachings, we can start to come to that awareness and the parts that we pushed. Really, it goes back to the Jungian idea of the shadow and the parts of us we don’t like that we’ve pushed into the shadow and then need individuation to kind of own the whole of ourselves. It goes back to that idea, but that itself is really based on the spiritual teachings of the soul, which originate in the Zohar.

Debbie Ford has a book about the shadow called The Dark Side of the Light Chasers. One of the things, too, that you were talking about Shabbat that reminded me—I had an episode on the show where Joe McQuillen was talking about communicating with his son who passed. He goes to do this in his son’s room. It seems like 3 AM is the best time to get the strongest signal. He calls it “thin places.” Shabbat is a thin place. It’s a time, of course, but it’s when you have more access to the upper words than during the rest of the week. It’s beautiful.

If we act in a manner that creates distance between ourselves and God, we are, in effect, tarnishing the name of God through our actions. Click To TweetIf our listener or viewer wants to learn more from you, The Practical Tanya, and all your other works, how would they follow you and learn from you besides that?

Thank you. I have a YouTube channel. There are a lot of teachings there. All my books are available on Amazon. I’m trying to be on the cusp between scholarship and just popular works. I don’t want to dumb it down so much that it loses its grandeur. I also don’t want to be so scholarly that it becomes only relevant to a few people.

Deep, but all too accessible.

If you try Jewish text, it could be challenging. I’m trying to reveal the authentic and original and make it accessible to people like myself. I always write to myself when I’m 16 years old, 20 years old, looking for something meaningful, spiritual, and intelligent.

Amazing. Your website is rabbichaimmiller.com. I really appreciate you being on the show. Thank you so much.

Thank you. We’ve covered a lot. That was pretty good.

Thank you so much. Thank you, listener. Go out there and make the world a better place. Reveal some light. We’ll catch you in the next episode. I’m your host, Stephan Spencer, signing off.

Important Links

Rabbi Chaim Miller

Amazon – Rabbi Chaim Miller

YouTube – Rabbi Chaim Miller

A Wrinkle in Time

The Body Keeps the Score

The Book of Gilgulim

The Dark Side of the Light Chasers

The Guide for the Perplexed

The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy

The Myth of Normal

The Practical Tanya

Joe McQuillen – previous episode

Billy Joel

Carl Jung

Dalai Lama

Debbie Ford

Rabi Dov Ber of Muzirich

Douglas Adams

Dr. Gabor Maté

The Baal Shem Tov

Joe McQuillen

Madeleine L’Engle

Maimonides (Rambam)

Rabbi Nissan Mangel

Nehunya ben HaKanah

Prince Harry

Rabbi Isaac Luria

Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai

Tanya

Akashic Records

Ana b’Koach Prayer

ChatGPT

Five Books of Moses

Gaia hypothesis

Hasidic Movement

Jewish spirituality

Malchut

Ohr Ein Sof, the Infinite Light of God

Shechinah

The Ten Sefirot of the Kabbalah

The Wanderers

The Zohar

Past Life Regression

Talmud

Douglas Adams – BBC interview

Checklist of Actionable Takeaways

About Rabbi Chaim Miller

About Rabbi Chaim Miller

Rabbi Chaim Miller was educated at the Haberdashers’ Aske’s School in London, England and studied Medical Science at Leeds University. At the age of twenty-one, he first began to explore his Jewish roots in full-time Torah study. Less than a decade later, he published the best-selling Kol Menachem Chumash, Gutnick Edition, which made over a thousand complex discourses of the late Lubavitcher Rebbe easily accessible to the layman. His 2011 compilation, the Lifestyle Books Torah, Five Books of Moses, Slager Edition, was distributed to thousands of servicemen and women in the U.S. Army. In 2013, he was chosen by the Jewish Press as one of sixty “Movers and Shakers” in the Jewish world. His latest works include Turning Judaism Outward, the first full biography of the Lubavitcher Rebbe, & the multivolume Practical Tanya, which has set new standards in the translation of Chasidic thought for contemporary readers. He lives in Brooklyn, New York with his wife, Chani, and seven children.

Disclaimer: The medical, fitness, psychological, mindset, lifestyle, and nutritional information provided on this website and through any materials, downloads, videos, webinars, podcasts, or emails is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical/fitness/nutritional advice, diagnoses, or treatment. Always seek the help of your physician, psychologist, psychiatrist, therapist, certified trainer, or dietitian with any questions regarding starting any new programs or treatments, or stopping any current programs or treatments. This website is for information purposes only, and the creators and editors, including Stephan Spencer, accept no liability for any injury or illness arising out of the use of the material contained herein, and make no warranty, express or implied, with respect to the contents of this website and affiliated materials.

LOVED THIS EPISODE

Please consider leaving me a review with Apple, Google or Spotify! It'll help folks discover this show and hopefully we can change more lives!

Rate and Review

About Rabbi Chaim Miller

About Rabbi Chaim Miller